- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

Liberating Concentration Camps - American GIs in World War II

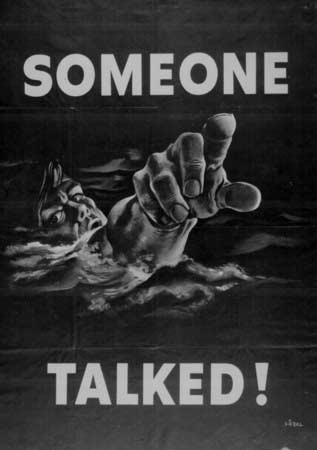

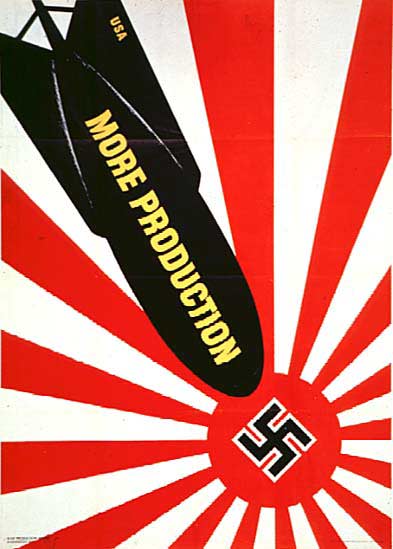

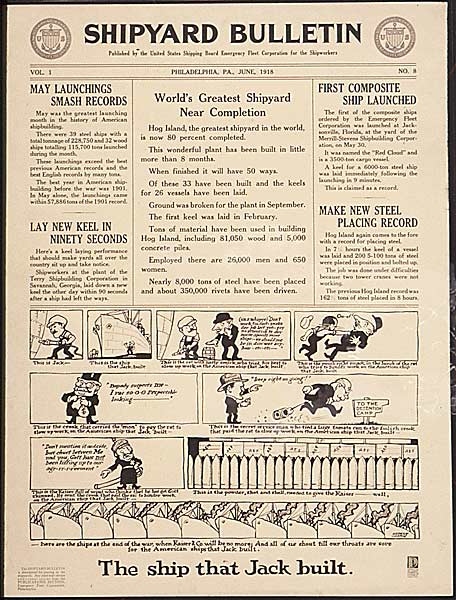

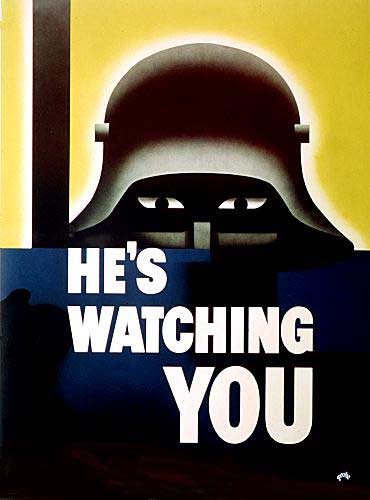

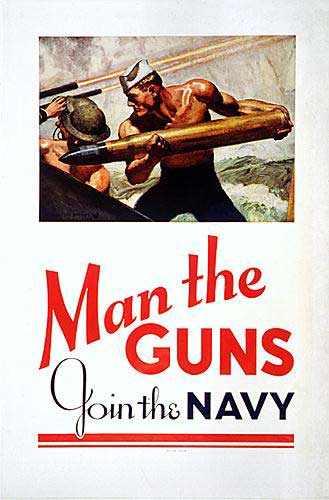

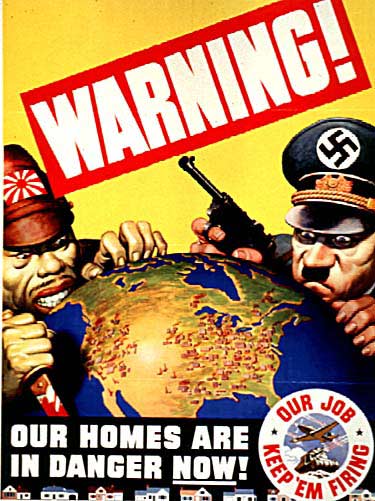

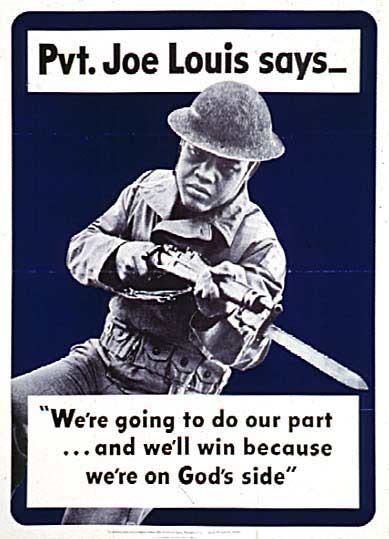

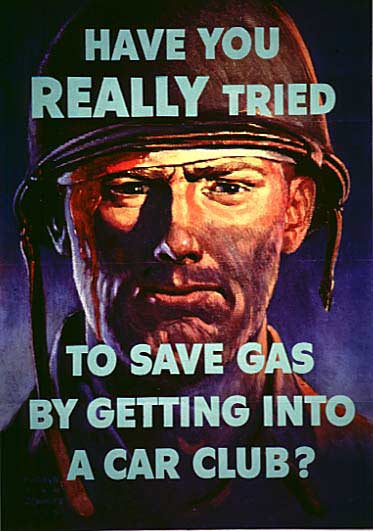

U.S. Posters and Photographs - World War II - National Archives

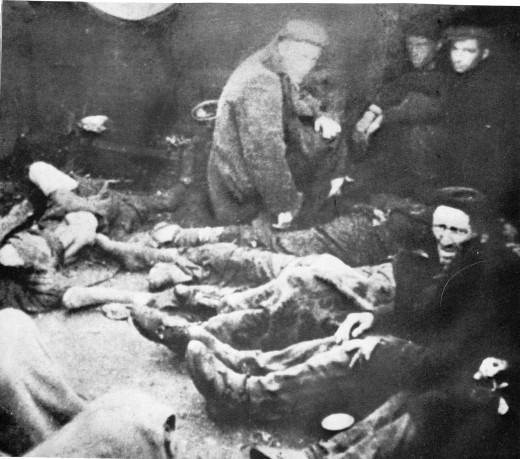

Starvation and Disease in the Concentration Camps

Not all inmates were physically capable of rushing up to GIs to request food; their physical strength varied greatly. Recent arrivals to camp might be, and often were, relatively healthy, but many long term internees were severely debilitated and near death. Officer Stoneking noticed many inmates who lacked the strength to walk steadily. "They were sitting down everywhere with arms outstretched to us."[1]

Lieutenant Colonel Joseph W. Batch of the medical corps evaluated the inmates of Dachau. About half were in "advanced stages of malnutrition. The wasting was extreme and many were so weak they were unable to walk. Practically all had the appearance of indifference and apathy indicative of mental changes."[2]

GIs were uniformly struck by the dreadful physical appearance of the inmates. "We came along with the hospital here to see what we could do about saving some lives....They are a pitiful sight....I could put my thumb and index finger around the average arm or leg, even at the thigh. They are so ill and thin it is indescribable...most are too weak to move...." In his book Dr. Brendan Phibbs recalled the condition of many of the survivors.

"Their faces were skulls, bones painted brown, and the fingers clutching the bread were like thick wires..... I had seen hundreds of people die of wasting diseases, of cancer, of terminal kidney or heart disease, of infections...but not in the wildest ravaging of a virus or a malignancy had I seen the human body reduced to the stages of these prisoners. Nothing in the lexicon of medical horrors could have so shriveled the flesh from around the bones and from under the skin."[3]

One of the great frustrations for regular soldiers and for medical personnel was the intolerance of the survivor's damaged intestinal tracts for normal food. In areas where food was quickly available and distributed, some survivors died immediately upon ingesting the food supplied by American soldiers.

This rich and concentrated food, perfectly adequate for those with healthy and non-traumatized digestive systems, constituted a severe shock to the digestive systems of the diseased and starved camp inmates. Nurses and doctors labored to find the proper balance of food, multivitamins, plasma for body proteins, and intravenous and oral fluids for each patient.[4]

Realizing that the ingestion of normal food was causing fatalities, medics and doctors began to caution GIs not to give their rations to inmates no matter how desperate or pitiful their physical condition. Military POW and DP reports confirm individual observations. "Information from recovered Displaced Persons indicated that conditions have recently been deplorable. In the majority of cases the liberated individual cannot assimilate the U. S. ration until after medical treatment due to prior undernourishment."[5]

Private William McConahey and other American soldiers described their frustration. "In the camps the sick were still dying. We couldn't save them. We tried to feed some of these people, and really we couldn't....You couldn't save them. We felt terrible! They were dying under our eyes! Nothing we could do because they were so close to death, and you couldn't feed them."[6]

There were also malnourished inmates just approaching the early stages of starvation who still possessed a modicum of physical strength and energy, and who posed control and order problems for the American military. These relatively healthy survivors at times fought over government food rations and struggled to get into food lines once the soldiers set up mess kitchens. Occasionally supply wagons and trucks were stormed by inmates desperate for food.[7]

In a number of camps soldiers witnessed ambulatory survivors fighting over and consuming raw meat--chickens, cows, horses.[8] Starving inmates also consumed items like cigarettes and raw flour. Major Aaron Cohn was at Ebensee. "There was a group of them [camp inmates] standing by the vehicle when a sack of flour burst open and half of it was spilled in the mud in the courtyard; I saw six men leap to the ground on their stomachs and lick the flour from the black mud and from the water...."[9]

Survivors whose starvation was more profound were too weak and listless to feed themselves even when food was abundant and readily available. Corporal Fred Mercer described a man he encountered in Buchenwald. The man was leaning huddled in a corner, too weak to stand or to eat. Surrounding him on the floor was a six month supply of food; apparently dozens of GIs who had seen the man left him their rations.[10]

Many survivors in the camps were equally debilitated; a large number of them weighed between fifty and seventy pounds when they were liberated.[11] The weight loss caused by prolonged starvation was also documented by examining and weighing inmate corpses. American surgeons found that adult male corpses usually weighed between sixty and eighty pounds. They estimated the loss of body weight at fifty to sixty per cent.

Weight losses of this magnitude are only comprehensible in the context of average daily caloric intake. Inmates at Dachau during the months prior to liberation were provided a diet containing approximately 600 calories per day. On this meager, imbalanced diet, they were required to perform hard physical labor in extremely cold weather with minimal clothing.[12]

Realizing that such severely wasted bodies could not tolerate regular food, soldiers, nurses, and medical corpsmen began to offer the survivors bland soup, thin gruel, or broth.[13] Blood transfusions, glucose injections, and intravenous drips were used with inmates whose systems could not tolerate soup or broth. As the patients slowly gained strength they were put on a diet of dilute cereal and milk.[14]

Based on his early experience at Dachau Dr. Laurence Thouin reported that some twenty to thirty patients died when he and his men administered glucose solution. They quickly discovered that the emaciated survivors could tolerate a diluted mix containing 75% water and 25% glucose solution. Sergeant Paul Marks, working with an Evacuation Hospital at Mauthausen, watched patients die because their veins had collapsed making intravenous feedings and injections impossible.[15]

American GIs encountered other problems as they tried to feed camp survivors. Army regulations and orders from administrative officers obstructed the flow of needed provisions in some areas. Dr. Phibbs was infuriated when he received orders not to feed concentration camp survivors on army rations. He sent numerous requests to 3rd Army detailing the shortage of foodstuffs and describing the condition of his patients.

Phibbs was also instructed not to remove food from nearby German warehouses or to use German livestock. The rationale offered was that the U.S. government does not steal or appropriate private property; armies are allowed to forage for food, which is not considered theft, but only to feed their own troops.

Unfortunately, while Phibbs was in need of food supplies for his typhus and tuberculosis patients, U.S. military dumps of rations sat on docks unused, and when they were put to use, it was often for profiteering and exchange on the local black market. Sufficient provisions were available for Phibbs' patients approximately four weeks after liberation. Lieutenant Colonel James Wilson also received orders from his superiors regarding use of army rations, but his orders were based on a different standard.

"We had to keep the displaced persons and the liberated prisoners separate because of messing arrangements. The [liberated] prisoners had to be fed army rations, and the displaced persons were fed off the land." A standardized American policy may have existed on paper, but it was not widely promulgated or enforced.[16]

On occasion American officers located and appropriated local food stores without the permission of their superiors. In many areas around the liberated camps, the general civilian population was not on the verge of starvation at the end of the war and liberators felt justified in taking local stores of provisions for the use of survivors.

Substantial and varied stocks of food were discovered in a great number of locations: a basement full of wheels of cheese, well-stocked canned foods factories, staples warehouses full of noodles, potatoes, soups, meat, and fresh vegetables, live cows and chickens.

Numerous official documents as well as individual GIs comment about the healthy and well-fed appearance of most German civilians. The striking contrast between well-fed civilians and the miserably emaciated survivors, helped contribute to the liberators' increased resentment and fury toward the German military [17]

Occasionally a GI would report rapid delivery of foodstuffs. Government trucks crisscrossed Germany delivering supplies to permanent hospitals, clinics, camps, schools, and makeshift tent hospitals set up in open fields. For example the 42nd Quartermaster Company headed for Dachau on 30 April 1945 and swiftly established division supply dumps at the railroad station.[18]

Reports from Dachau detail the magnitude of the supplies needed. "An immediate survey was made of food requirements by Lieutenant Rosenbloom within the camp and by Captain Taylor outside the camp, to determine possibilities for local provisioning. These rapid surveys indicated the camp had a food supply sufficient for 4 days, with very little available locally. Request was made to Seventh Army by telephone to provide automatic rations for 41,000 persons daily (population of camp was 31,000 plus 9,484 at the subsidiary work camp known as Allach)."[19]

Another report describes the changing and increased caloric intake for the average Dachau survivor. "On 29 April inmates received about 600 calories, unbalanced. U.S. control started with 1,200 calories which was shortly increased to 2,000 calories."[20]

Food requirements might vary significantly from day to day and week to week depending on the departure of reasonably healthy survivors and the arrival of recently liberated and desperately ill inmates. At Salzwedel "the Frenchmen appropriated a truckload of food and took it to the girls camp which needed it badly since about 1,500 women had arrived at the camp in the previous two weeks without any commensurate increase in the food ration."[21]

At other locations supplies were not readily available. A report from Mauthausen stressed the urgency of the need. "Immediate increase of diet is necessary, but is impossible due to the lack of transportation and inability to secure enough meats, flour, cereals, rice, potatoes, and other food."[22]

Often liberators did whatever was necessary to procure food for the survivors in their care. Men of the 802nd Field Artillery Battalion stationed near Nordhausen canvassed the local German population gathering foodstuffs for the Russian survivors of a Nazi slave labor camp.[23]

What was necessary in some camps was the restoration of a safe water supply. At Mauthausen-Ebensee GIs managed to get a bakery and soup kitchen operational; somehow they scrounged 2000 bowls and spoons for their inmates to use. At Nordhausen a working bakery lacked only a water supply.

Military Government reported that personnel "transported 500 gallons of water to a bakery...bread to be distributed to three temporary hospitals.... An additional 1,500 loaves can be procured daily...provided water is transported to the bakery."[24] As rapidly as possible, and using both American and German supplies and equipment, the GIs mobilized to provide sustenance for the remaining camp inmates.

As we have seen American soldiers worked in the concentration camps and with survivors to maintain order, and provide food and minimal medical care. Officers were responsible for general camp administration, duty assignments, requisitioning supplies, and keeping the peace. These were the primary and essential goals during the first two to four weeks. Thereafter, officers would bring in engineering battalions to restore water lines, build sanitary facilities, bury the dead, and participate in massive and gruesome cleanup efforts. Additional medics, orderlies, nurses, and doctors would arrive to work directly with the sick, injured, and starving survivors.

The need for medical care was so great that many regular soldiers were given rudimentary training on the spot and became integral parts of the medical teams. Chaplains, and their assistants, provided spiritual and emotional comfort, performed religious services, typed and circulated lists of survivors' names, and wrote letters to survivors' family members, often working side by side with the medical staff. But all of these efforts would be delayed until adequate personnel and supplies had been diverted to the camps. The American military command was not prepared, or had not prepared, for immediate response to the situation found in most Nazi concentration camps.

End Notes ~ Citations

[1]Stoneking, DMC.

[2]LTC Joseph W. Batch, Medical Corps, Inspection of Dachau Concentration Camp, 2 May 1945, Entry 54, RG 331.

[3]Leslie G. Brown, letter II; Leslie G. Brown, Memoir, 50; both in the World War II Collection, MHI; Brendan Phibbs, The Other Side of Time: A Combat Surgeon in World War II, (Boston: Little, Brown and Company), 317-319, (hereafter cited as Phibbs, Combat Surgeon).

[4]116th Evacuation Hospital, Semi-Annual Report, Jan-June 45, RG 407.

[5]Coulston, DeProphetis, Pincus, Gratz; Wehmoff, 3, Montesinos, 5 Emory; Darr, 4, JCRC; Stein, James, USHMM; Robert Gravlin, 3rd Army Division Papers, MHI; Gerald McMahon, Riding Point for Patton: The 5th Infantry Regiment in World War II (LeRoy, New York: Yaderman Books, 1987), 32 (hereafter cited as McMahon, Riding Point); PFC George Porter, B Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 71st Infantry Division, in McMahon, Siegfried, 466; POW and Displaced Persons Division, Report, April 1945, RG 332.

[6]McConahey, JCRC; Dowdle, 77, DMC; Paul B. Marks, Medic, 99th Infantry Division, World War II Collection, MHI (emphasis original).

[7]Milbauer, Peretz, USHMM; Walters, Gratz; Theodore Draper, The 84th Infantry Division in the Battle of Germany, November 1944-May 1945 (New York: Viking Press, 1946), 244; Gavin, 82nd Airborne Division, 289; PFC O'Neill, B Battery, 608th Field Artillery, 71st Infantry Division, in McMahon, Siegfried, 467.

[8]131st Evacuation Hospital, Organizational History, 1946, 81, RG 407; Manning, 75, DMC; Fletcher, 71st Came, 10.

[9]Cohn, 7, Emory; Fletcher, 71st Came, 10.

[10]Mercer, 7-8, Emory.

[11]Ralph Mueller and Jerry Turk, Report After Action: Story of the 103rd Infantry Division, (Innsbruck: Wagnerische Universitats-Buchdruckerei, 1945), 134; Herbst, USHMM.

[12]POW and Displaced Persons Division, Reconnaissance Report, April 1945, RG 332; SHAEF FWD G-5, Incoming Message 7th Army, 8 June 1945, RG 331.

[13]Elizabeth Holey, 1, Q-Ast; Seibel, Ward, USHMM; Adzick, 2, Q-Ast.

[14]Buchenwald Parliamentary, RG 319; James Gavin, On to Berlin: Battles of an Airborne Commander, 1943-1946, (New York: Viking Press, 1978), 289; Combat History of 3rd Armored Division, RG 407; SHAEF FWD, Incoming Message, 12th Army Corps, 9 May 1945, RG 331.

[15]Thouin, 5, Emory; Marks, 2, Q-Ast.

[16]Phibbs, Combat Surgeon, 328-334; Wilson, Q-Ast.

[17]Ambrose, Band, 270; Seibel, USHMM; Fletcher, 71st Came, 11; Malachowsky, Liberators, 31; Nost, 8, JCRC; G-2 BID Report, Mauthausen Concentration Camp, RG 319; Keith Winston, V-Mail: Letters of a World War II Combat Medic, (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 1985), 208, 216; HQ, 116th Evacuation Hospital, Unit History, May 1945, RG 407; POW and DP Division, Reconnaissance Report, April 45, RG 332; G-5 Problems in First U.S. Army, 9 May 45, RG 407.

[18]Stoneking, DMC; Walters, Gratz; 42nd Quartermaster Company, Narrative, April 1945, to Adjutant General, Washington, DC, RG 407.

[19]XV Corps, "Action Against Enemy Reports--After, April 1945, Annex 5/ G-5 Historical Data, 9, RG 407.

[20]SHAEF FWD G-5, Incoming Message, Seventh Army, 8 June 1945,

RG 331.

[21]Ninth Army, 4th Information and Historical Service, Salzwedel, April 1945, RG 407.

[22]131st Evacuation Hospital, Report Mauthausen, 14 May 1945, RG 407.

[23]History of 802nd Field Artillery Battalion, April 1940 to May 1945, 61.

[24]Buch, USHMM; 131st Evacuation Hospital Report, Mauthausen Concentration Camp, 13 May 1945, RG 407; Military Government Report, DET H6B3, Nordhausen, 12-15 April 1945, RG 331.